If you’re the parent to a baby just beginning their journey into starting solids, you’ve probably heard from someone, whether it’s been me, a family member, your baby’s pediatrician, or another dietitian on Instagram, that you need to limit your baby’s salt intake. It’s a common message that gets repeated over and over. And the basis for it is simply that your baby’s tiny body cannot handle as much sodium as adults can – so limit it wherever you can!

However, often this message gets said so frequently, and really emphasizes the dire nature of serving your baby any amount of salt, that you panic. As a parent, you want only what is best for your child, and if health care professionals are repeatedly telling you that salt is not it, and can in fact have dangerous consequences for your baby, the anxiety to adhere to their calls for restriction is real. And let’s face it, salt is everywhere, so being able to easily restrict your baby’s salt intake can seem impossible. All in all, this adds up to create a lot of stress and pressure for new parents just learning how to feed their babies.

Today, I’m talking about whether that added stress and pressure is really called for, or if perhaps the limits placed around salt intake are a bit exaggerated and, quite frankly, not based on a whole lot of research. I had the pleasure of speaking with Lily Nichols, RDN who is known for diving into the research to get to the truth of the matter, and she had a lot to share about this topic, and about what she found that the research actually says.

So, let’s get into what she has to say about it (you can listen to the full interview below as well).

All the research to back up the upcoming statements can be found here).

Salt guidelines for adults

There are so many myths out there when it comes to salt for adults. The guidelines are perpetuated and outdated, so it’s no surprise. We’ll begin by going over what Lily Nichols had to say about salt for adults, and then move into the recommendations for babies.

Salt is one of those nutrients that a lot of people have been told they should avoid. It’ll make you puffy and bloated, it’ll spike your blood pressure, it’ll damage your heart and arteries, it’ll damage your kidneys, it’ll lead to stroke, you name it. And we have a lot of epidemiological evidence where they look at population wide rates of disease, and then try to correlate it with very specific factors that say salt is basically killing us all. But, actually many of those claims are unfounded.

You need salt for electrolyte balance. This keeps your heart ticking, and your cells talking to each other. You need it for maintaining correct plasma volume in your bloodstream. So in other words, for regulating your fluid levels. You need it for neural signaling so you can think straight and move your muscles in the right way. You also need it when you’re under stress, this is when your body goes through more salt. When you eat low carb, your body requires more salt because you spill more out in your urine when your insulin levels are better controlled. You also need salt to maintain adequate stomach acid. The chloride of sodium chloride helps you make hydrochloric acid, which ultimately helps you digest your food and absorb minerals, and vitamin B12, and kill off pathogenic bacteria. So salt is something that is a bit of a new thing for us to think that it’s evil. If you go back a hundred or 200 years, and certainly we were consuming a lot less processed food back then, so probably less salt as a whole, but salt wasn’t looked at as the enemy then.

One of the myths is that salt supposedly raises your blood pressure. Well, that’s not always true. Only about 25% of the population is salt sensitive, and actually 15% of the population will have increases in blood pressure if they eat too little salt. So yes, there are some people who have salt sensitive hypertension, where they do need to be careful about their salt, but that’s not the majority of the population.

The other myth is that people think if you eat less salt, it’s healthier automatically. But actually, there’s what they call a J-shaped curve relationship with salt intake and cardiovascular risk. This means if you eat too little, or an extreme ton of salt, you’re going to have a relative increased risk of cardiovascular disease either way. But in the middle of that, there’s actually a lower risk of heart disease. So essentially there’s kind of a sweet spot.

There’s another myth that if you eat too much salt, it’s going to damage your kidneys. But in fact, our kidneys are able to excrete fairly large sodium loads. There’s even a book for people who want to dive into this in more detail, called “The Salt Fix” by a doctor/cardiovascular researcher. It goes into a lot of this in more detail, so I recommend that.

Another thing is for people who have salt sensitivity and therefore need to watch their salt intake, the assumption is that their problem is solved if they decrease salt consumption. Basically, if you just eat less salt your problem is solved because this is an issue of salt and only salt. But actually, salt sensitive hypertension has more to do with your blood sugar, than it does with salt. So, if your blood sugar is elevated, and particularly if you’re eating a lot of refined carbohydrates and fructose, that can create salt sensitive hypertension. It’s not the salt necessarily, it’s the over-consumption of refined sugars and fructose, leading to elevated insulin levels, leading to salt sensitivity. It’s a different mechanism. We’re blaming salt for something that’s really caused by blood sugar issues; it’s just all so intertwined. You have to look at things from a holistic perspective, whereas we’ve traditionally been so used to looking at things nutrient by nutrient, in isolated ways.

Myths about salt intake for babies

I think after seeing all those myths with salt and adult health, it made it so much more obvious that there are probably some myths when it comes to salt and baby health as well. Some of the most common arguments for avoiding salt in baby food is that their kidneys are too immature to process the excess salt, and that they’ll develop this obsession or have more of an affinity for salty foods. But what are these arguments really based on?

These questions are what led Lily to write her salt and baby food post. The warnings about sodium for babies sound extremely dire. And there are professionals, who tend to be very loud on social media, who frequently post things like, “Choose this instead of this…because salt”, “Choose this over this… because salt”, or “Is your baby getting too much salt?” Everything is fear-mongering around salt. Because Lily’s work is mostly preconception, prenatal and postpartum, she saw this and thought there must be some evidence that she wasn’t aware of. People ask her to dive into some of these topics because she has kids, or they’ve worked with her in some capacity and now have kids themselves, and are confused because the advice on feeding kids is opposite to her advice of how they should eat. They find that Lily’s advice worked so well for them during pregnancy and postpartum, but then are wondering if they need to completely switch how they’re cooking in order to feed their kids safely.

The interesting thing about all of this is that the evidence behind the supposed harm is almost entirely lacking.

What does the research say?

When looking at salt and infant kidneys in the research, like a lot of the guidelines that exist, you have to look at what the origin is of that guideline and ask yourself “What is the origin of this specific number? Where did this come from?”. Because what you tend to see is that people grab onto a recommendation, and then the literature will just sort of incestuously cite that recommendation from whoever originally said it, or just cite it from some other paper from five years ago. And you go to that paper from five years ago, and you’re like, well, where did that come from? And it goes to a paper from two years before that. Well, where did that come from? It goes to a textbook. Well, where did that come from? And it’s hard to find.

Debunking the myth that excessive salt from food will cause kidney failure in infants:

What Lily was able to find on sodium intake and infant kidneys, was that the original fears seem to stem back from a study in the 1940s, where they gave both infants and adults an IV solution that was 40% sodium chloride. Then they monitored urine output. From this, they determined that infants were not able to excrete the sodium load in their urine to the same degree as adults. However, other studies have examined that study in detail, and found that they actually didn’t measure sodium in those studies. All they did was measure urine volume. Now, urine volume as a proxy of kidney function is invalid, especially for infants, because we don’t know the standard rate of urine flow for infants. It’s literally an arbitrary number because you can’t measure it easily, because infants are in diapers and it’s hard to extract the urine from diapers. And in this study, they never extracted the urine from diapers to measure the sodium in it, to see if they actually excreted the sodium load or not.

Now we have studies, from the early and mid two thousands, showing that you really can’t measure sodium from infants, because it’s usually done via a 24 hour urinary sodium collection. You collect urine for a full 24 hours, and then measure the sodium content in that urine, which provides a ratio of sodium to the amount of fluids. They can’t do that in infants because you’re not collecting all of an infant’s urine. Maybe if you found somebody who was doing an excellent job of elimination communication, where they’re catching all of the pees on the potty, you’d be able to measure it, but so far…nobody’s done that.

Debunking the myth that babies commonly get hypernatremia from salt in food:

What Lily found especially interesting was that, it’s very, very hard to find studies on high blood sodium levels (called hypernatremia), in infants. So the concern is that your baby’s going to get so much sodium that they can’t excrete it, and the sodium is going to build up in their bloodstream, or in their body, and cause harm. Just as we expect sodium to cause harm to the arteries or kidneys of adults. However, what you find more is hyponatremia in babies (low blood sodium levels), much more commonly than hypernatremia. And it’s mostly from infants who are not able to obtain enough fluids and food, whether they’re breastfed or formula fed. They’re essentially not eating (drinking) enough milk, and so when they’re dehydrated, their body will try to conserve sodium to also try to conserve any fluids. And thus, you run into this issue. But, she was only able to find one study on hypernatremia, and that was from an infant who received an improperly manufactured infant formula, which had eight times the usual amount of sodium. Even that infant did not have kidney damage necessarily. It is a medical emergency, if you have hypernatremia…it’s just exceedingly rare because your body can excrete the sodium.

debunking the myth that a baby’s kidneys at 6 months of age can’t excrete sodium well:

In addition to that, we also need to look at the age of the infants that were participating during these studies on sodium. If you’re looking at an infant who’s below the age in which you introduce solids, and they’re solely getting all of their sodium from breastmilk or formula, it’s a different scenario because the kidneys mature at different stages. I’ve seen studies that suggest that by four months, or at the very least one year, the infant kidney is mature enough to excrete a sodium load as efficiently as an adult. So, if we’re looking at these differences in blood sodium levels in infants that are one month old or two months old, does that have any bearing on an infant who’s six months old and being introduced to solids, and they’re having their one meal of the day, which is maybe a teaspoon of food, and we’re concerned that there’s a tiny sprinkle of sodium in there, is that really a concern? The main point here is that we’re not comparing apples to apples in this scenario, because the kidneys are at a different state of maturation at six months of age.

So, to be clear, there are precisely zero case studies in the literature showing excessive sodium consumption of complementary foods in infants six months of age, or older, that is linked to kidney damage. There are none…out of all of the hypernatremia cases Lily found! All cases of high blood sodium levels, dating all the way back to the 1970s, were in young infants, usually around 10 days of age – no more than 21 days of age. These were all from inadequate consumption of their breastmilk or formula, resulting in dehydration. In these cases, hypernatremia is a result of dehydration period, or dehydration caused by some sort of infectious disease that causes diarrhea, where they’re losing a bunch of fluids…but essentially it’s from dehydration, not over-consumption. And again, can we equate that data from 10 day old babies to six month old? In her opinion, no.

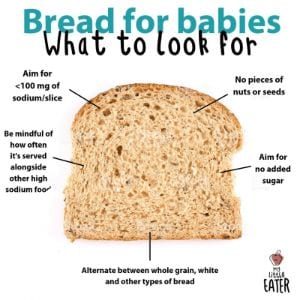

Current guidelines for sodium intake for babies

There’s so many things to try to watch out for, and include, and just navigate when starting solids, so salt intake is almost like this extra task that maybe isn’t fully necessary to worry about. The official recommendations, according to all those major regulatory bodies, is about 400 milligrams a day, but that includes the amount of breastmilk or formula that they’re consuming. Which means, it’s about 200 milligrams of sodium per day that would come from food, with another 200 milligrams coming from breastmilk/formula. And, because I’ve learned so much about this from Lily Nichols, I mention in my Baby Led Feeding online course that we don’t have full research to say exactly how much is too much. We just have basic, basic, basic, preliminary studies, so we don’t have enough research. It’s assumed that babies can’t handle a lot of salt, so we try to keep it around 400 milligrams a day.

Because of this recommendation, I always get parents that worry if their baby is going to be ok if they had a bite of their pizza, or something like that, since it has more sodium than recommended for one day. And yes, 100%, they’re going to be okay. Generally, I recommend you try and average things out. If you give them some high sodium foods one day, then maybe you just reduce the amount of sodium the next day. But additionally, what Lily is suggesting is that the recommendation of 400 milligrams a day isn’t even really based on anything.

Debunking the daily recommended amount of salt for babies:

The first thing that Lily looked at with infant salt was where was the sodium limit for babies coming from, and how was that set? It was interesting that what she found was that the sodium guidelines for infants are what’s called an adequate intake level, or AI, and guidelines only opt for an adequate intake level when there is not enough evidence to set a more accurate guideline, such as an estimated average requirement or a recommended daily allowance.

So in a nutshell, adequate intake is just the daily average nutrient intake based on estimates of what healthy people consume in their diet. It’s assumed that because these people are healthy, then their intake of that other thing, in this case salt, must be adequate. With infants, the way that they looked at that was by determining the sodium levels in breastmilk.

For infants 6 months and younger, the AI for sodium is set on the amount that’s in breastmilk. For infants older than 6 months, they have a 6 to 12 months recommendation, that is based on the amount of breastmilk they’re consuming, assuming that there is a certain level of sodium in that breastmilk, plus a certain amount of complementary food. Lily couldn’t find where they describe what the complementary foods are that they use to estimate the average amount of sodium they’re taking in. So that’s another guesstimate.

But, she did want to look at the breastmilk part because she’s done pretty extensive research into the variable nutrient levels in breastmilk, and particularly how maternal intake of nutrients impacts the nutrient values in breastmilk. So let’s go through the research on that.

Lily found that the sodium levels in breastmilk can vary a lot. Actually, one of her favorite breastmilk nutrient content researchers, Dr. Lindsay Allen, has been on some of these committees trying to push for change on the adequate intake level because it’s just not evidence-based. They chose a very small subset of American women and averaged the sodium level from that subset of women. Lily found many different studies showing a wide variation of sodium levels in breastmilk, ranging anywhere from only 50% higher than this group in the US, to pretty similar to the US, to 15 and a half times higher than what the US level was set at! And so, we’re making these assumptions on just bad data, or inadequate data, because the level that they went with was really low compared to what you see in a lot of these other studies. If we’re even going to set an AI at all, it should be a range, and not this one specific level.

Moreover, the breastmilk sodium concentration can change day-by-day, hour-by-hour. It might even have differences based on a woman’s ethnicity, or her diet. There was one study that showed Turkish women consume more salt than the average American, and that was the study that had a couple samples that were really high in sodium. There was also a study done in Japan, which generally has a pretty considerable sodium intake as well, however their sodium level in their breastmilk wasn’t as high as in the Turkish women.

We also need to think about our sodium levels changing at different stages of lactation. The suggestion in the US guidelines is that sodium levels in breastmilk decrease over time. But Lily found other data showing that sodium levels in breastmilk increased over time. So, in other words, it’s all just a giant guesstimate. We have no idea how much sodium our babies are getting from breastmilk. There hasn’t been a study that compares women who are getting X amount of sodium, to a medium amount, to a high amount of sodium, and how that impacts the sodium levels in their breastmilk. It simply doesn’t exist.

So, what’s the conclusion?

It’s just silly to get hung up on this very specific number of 400 mg of salt per day that a baby has to be limited to, and with all the parents out there who are already totally overwhelmed and stressed out about trying to figure out how to introduce foods to their babies, prevent choking, and watching for allergies, and preventing picky eating etc…having them add up the amount of sodium that their baby is getting when they’re literally eating maybe a teaspoon of food is unfair, and may actually be actively doing harm because of the anxiety it causes.

We know how many diets and different types of ways of eating there are all around the world, and in cultures everywhere. When we can see how varied salt intake for babies is all around the world, and how they’re still healthy and without any kidney damage…we need to question the validity of this AI level that was put in place. There’s so much more research to be done in this area.

Now I’m not saying that we shouldn’t watch our salt levels but, generally, I would say it’s more about the quality of the food you’re eating than counting up how many mg of salt is going into your family’s homemade meal. I’m a big proponent of whole foods, and I know that when you go to foods that are more processed, you’re generally going to be going towards foods that have a whole slew of other ingredients that are not going to be good for your health, that also do have a lot of salt. So generally, yes you definitely want to avoid those.

But, if we’re talking about giving your baby a mainly whole foods diet, where most things are made from scratch at home, with the occasional bite of a pizza that your baby gets, for example…it’s not going to make or break their diet. It’s not going to cause them to have some kind of horrible disease. You just have to be sensible about it.

To put this into perspective, about 75% of the sodium consumed, in the US diet, is from processed foods, and only 10% is what’s added during cooking or at the table. I think, especially for families who are consuming a lot of processed foods, it’s probably a good idea to watch the processed foods, not just because of the sodium, but because of that and all the other stuff. If you’re mostly cooking from scratch, and you’re worried that you put a sprinkle of salt on the broccoli before you served it to your baby and now you’re thinking you have to throw it away and prepare a new one that doesn’t have any salt…no. We also have data showing that if you provide kids with vegetables that have a little salt and fat on them, they’ll eat more of them. So if we want our kids to learn to enjoy foods that are slightly bitter, salt helps mask bitter flavors, and so you can get your little ones eating broccoli, asparagus, and kale, and all sorts of more complex flavors, if they taste good.

I also really wonder how many people in previous generations were going out of their way to prepare completely separate meals for their infants. I don’t think that they were. Back in the sixties, when they started getting concerned about sodium levels and baby food, the average infant was consuming 2300 milligrams of sodium. They were just giving them traditionally canned foods, so canned vegetables, canned meat, like Spam, and all the canned stuff that’s so high in salt, they were getting a ton of salt. If it were as dire as it’s made to sound, we would have a whole generation of people walking around with severe kidney disease because they were getting just extreme quantities of salt. I don’t think we should be giving babies 2300 milligrams of salt, but there was definitely a time when we had switched from homemade baby food to pushing this 1950’s style of everything being canned and pre-made, where babies were getting a lot of salt, so I think it’s all about perspective.

The biggest takeaway here is we’re all for healthy diets in general, we’re all for doing what you can to make your diet, and your baby’s diet, as best as you can make it. But, that being said, we all need our food to taste good. We all have a life to live. There’s literally no good evidence that there’s going to be any development of kidney disease, or any dire outcomes, from having a little bit of salt in your baby’s food. So, don’t stress, eat generally a whole foods diet, like how I teach you in the baby course about what kind of foods to serve, but you don’t have to worry to the extent that so many of us are worrying about every little speck of salt and milligram that your baby takes in. I hope this is going to offer a lot of peace of mind for everybody.

If you’re looking for more guidance on what and how to feed your baby solid foods, my Baby Led Feeding course can walk you through everything you need to know. It covers how to know your baby is ready, what nutrition they need, how to safely serve all foods, the difference between gagging and choking, and so much more!